Colorado’s Medicaid program, Health First Colorado, faces a suite of long-term financial problems likely to grow even more severe over the next few years. Some officials will hold the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), federal legislation signed into law last July, responsible, but Colorado’s Medicaid program has been on an unsustainable path for years.

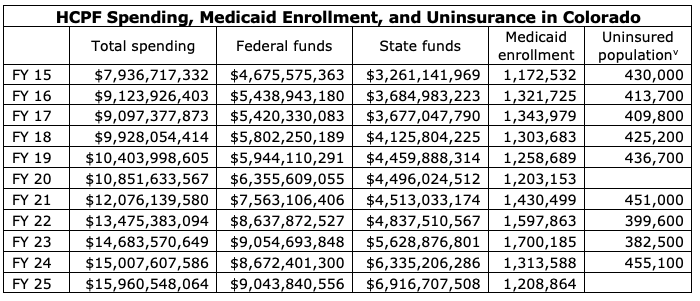

Health First Colorado is administered by the Department of Health Care Policy and Financing (HCPF), whose footprint in Colorado’s government has been growing for decades, especially since the state opted into Medicaid expansion in January 2014. High costs, strict regulations, concerns about quality of care, and fraud all plague Health First Colorado. HCPF’s budget has consistently risen faster than other state spending even through periods of declining Medicaid enrollment—between 2015 and 2025, HCPF spending doubled while the rest of the state budget grew by 64%.[i]

Recent policy changes are responsible in part for HCPF’s extreme spending obligations. The Colorado legislature enacted 182 new health care bills between 2019 and 2025, many of which expanded HCPF and raised the costs of providing public insurance. These bills created new bureaucracies, expanded covered services, and added regulations on public and private providers. The incremental cost of these new policies totals at least $858 million per year in state spending alone.[ii]

Beyond the bills specific to the healthcare sector, legislators have enacted a total of 350 new bills that affect hospitals directly or indirectly through environmental regulations, workforce laws, or other matters.[iii]

Throughout the 2026 session, legislators are likely to propose bills that address the prospective impacts of the OBBBA, whose changes to Medicaid will not take effect until 2027. Their ability to enact more policies like those described above may be limited this year by statewide revenue shortfalls and concerns about the OBBBA.

HCPF Spending and Medicaid

HCPF is Colorado’s designated agency for receiving and allocating federal Medicaid funding. The Department also receives funding for Child Health Plan Plus (CHP+), which covers children of some low-income parents and pregnant women who do not qualify for Medicaid.

As the organ of government responsible for health-care spending in Colorado, HCPF has requested and received dramatic increases to its budget over the last decades. Before 2011, education received a larger share of state funding than health care, but HCPF came to dominate the budget through Medicaid expansion, new health insurance programs, and a deepening pool of coverage requirements and other laws upheld by state spending. In just the last 10 years, its spending doubled from $8 billion to $16 billion while other state spending rose by just 64%.[iv] HCPF’s spending was nearly 37% of the state’s operating total in fiscal year (FY) 2025, whereas the Department of Education, the next-largest entity, spent 18%. The agency, whose primary function is managing Health First Colorado, continued to grow even during rapid declines in Medicaid enrollment since 2022. High medical inflation, hundreds of new health-care regulations, and rising full-time–equivalent (FTE) employment contribute to this trend.

CSI’s analysis suggests that much of HCPF’s last decade of spending increases could have been avoided in the absence of expansive policy and other nonessential spending. The agency’s total spending growth over that period, 101%, is higher than the combined growth rates of Medicaid enrollment, medical inflation, and obesity (a proxy for public ill-health).[vi][vii][viii] In the absence of some other nondiscretionary cost driver, this means that HCPF is spending more than is strictly necessary to deliver its services.

Had the agency, with respect to Medicaid caseloads, inflation, and public health, budgeted in FY25 as it did in FY15, it could have spent as little as $10.8 billion—still $2.9 billion more than in 2015, but $5.1 billion less than its actual spending. Some aspects of HCPF’s administration, like its FTE employment level, grew at exceptional rates between those two years, but the Department’s administrative spending remained near 4% of its total budget throughout. Some aspects of HCPF’s administration, like its FTE employment level, grew at exceptional rates, but its total administrative spending remained near 4% of its budget throughout the decade.[ix] What changed the most over that period was policy. Lawmakers enacted 182 new health care bills between 2019 and 2025 alone that added $858 million to the annual state burden and a similar amount to the state’s use of federal matching funds.

Program Management

At the same time its budget was rising, HCPF left millions of dollars of federal funding on the table that could have helped hospitals and improved patient care. Specifically, HCPF failed to maximize federal matches for reimbursing the costs of hospital treatment provided to Medicaid patients. Other states achieved the full match but Colorado, under HCPF’s management, chose not to.

While leaving federal funding for providers on the table, HCPF increased its own administrative overhead substantially. Data show that, from FY18 through FY24, Medicaid enrollment rose by 7.6%. During this same period, HCPF’s total FTE employment rose by 72%—an increase equivalent to 339 full-time staff—amid only a modest increase in case volume.[x] Meanwhile, spending by the Executive Director’s office doubled from $252 million to $506 million.[xi]

These patterns have generated a tremendous amount of spending on HCPF functions other than patient care and a sizeable increase in the level of uncompensated care hospitals have to provide. The following subsections highlight some changes to HCPF functions that could make the state’s healthcare system more efficient before the OBBBA comes into force.

State Directed Payments

Colorado has historically not taken advantage of State Directed Payments (SDP), which allow state Medicaid programs to instruct managed care organizations (regional healthcare networks that manage Medicaid members’ insurance plans) to make additional payments, supported by federal matching, to health care providers for the sake of improving access to care and quality. In an effort to reduce federal spending, the OBBBA significantly restricts Medicaid SDPs by capping them at 100% of the Medicare rate for expansion states and 110% for non-expansion states.[xii]

Although SDPs have been available to states since 2016, HCPF did not seek to capitalize on that source of federal funding until the last possible moment. On June 24, 2025, with just days to spare before the OBBBA was signed into law, the agency published a proposal for a SDP program to supplement funding for the Colorado Healthcare Affordability and Sustainability Enterprise.[xiii]

RAC Audits

HCPF is responsible for ensuring that Medicaid expenditures are appropriate and that providers throughout the state are billing properly. Payments should only be made for services that are provided, medically necessary, accurately coded, and billed within proper timeframes. Colorado participates in the Recovery Audit Contractor program (RAC), and it is one of only 18 states with a Medicaid RAC audit program. HCPF outsources this audit function to a third-party contractor. The goal of the RAC auditor is to audit claims, identify improper billing and errors, and then recoup funds from a given provider.

This program benefits providers and the rest of the healthcare system if done correctly and in good faith. An independent audit completed in 2024, however, identified many shortcomings in Colorado’s RAC audits.[xiv] Some, but not all, of these issues were addressed during the next legislative session by the signing of SB25-314.[xv] Among the problems found by the 2024 audit are the following:

- HCPF did not verify that RAC staff have contractually required credentials (resolved by SB25-314).

- HCPF has not ensured that its RAC auditor offers provider outreach and education as the contract requires, reducing its effectiveness at improving provider billing practices.

- During the five years between 2019 and 2023, RAC auditors recovered approximately $84 million in overpayments to providers, $73 million of which happened in just 2022 and 2023. Hospital leaders appeal or contest a large share of these overpayments.

- HCPF paid the RAC auditor 18% of overpayments identified, as opposed to amounts collected, which may incentivize the RAC auditor to be less scrupulous when attempting to find overpayments. The 18% premium was higher than that offered in any other U.S. state until SB25-314 capped it at 16%.

- When the RAC auditor identifies underpayments, correct amounts are not returned to providers. Colorado is the only state that does not fully reimburse hospitals for underpayments.

- The administrative burden on providers responding to RAC audits, which must be done in a short window of time, was excessive. Under SB25-314, providers can now be audited only three times per year.

- Providers have the ability to appeal against RAC findings, but the process is costly, inefficient, and often fruitless.

- RAC audits in Colorado covered a seven-year period. Only one other state allowed a period this long. SB25-314 now restricts Colorado's maximum look-back period to three years, bringing it in line with most other states’.

Although SB25-314 addressed many of the biggest problems with RAC audits in Colorado, there remains much that could be done to ease providers’ burdens and restore confidence in the program. The purpose of RAC audits should not be just to correct irregularities but to educate providers and foster transparency, functions that the state’s punitive approach has so far neglected.

Hospital Transformation Program

The Hospital Transformation Program (HTP), a HCPF-led initiative to improve access, quality, efficiency, and integration across the healthcare continuum for the Medicaid program, began in 2021. It penalizes and rewards hospitals based on performance standards that it sets; its penalties are expected to increase after this summer, especially for some rural hospitals, if the program is renewed.

Survey responses across the 85 participating hospitals throughout the state suggest that some aspects of the HTP have been beneficial while others are burdensome and duplicative of other regulatory projects.[xvi] Hospitals already have robust quality programs under standards put forth by Medicare, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals, the Colorado Department of Health, and other regulatory bodies. Some facilities believe that patient care has improved and that relationships with Regional Accountable Entities (RAE) and the Health Information Exchange (HIE) have somewhat improved, but hospital leaders also largely say the program has not helped them achieve health-related social needs, which is one of the stated aims of the program.

Hospital leaders also claim that HTP performance measures have led them to prioritize those measures over more meaningful initiatives that better address the needs of their patients and help improve quality. In addition, the substantial administrative burden imposed by the HTP has diminished the desired impact of the program and caused hospitals to spend extra time and resources to meet documentation requirements. Many hospitals believe that the measures imposed by the HTP do not align well with other state and federal quality initiatives. This problem adds further to the administrative and cost burdens.

Although many providers believe HCPF has been helpful at understanding their needs, there are many flaws in program administration. Hospitals report that they had limited understanding of the data they received at the start of the program and largely lack the information technology resources needed to collect the data that the program requires of them. Furthermore, hospitals report that they do not receive timely data from the state to support real-time improvements. Also of concern to providers is a sense that some of the program’s standards change suddenly and unexpectedly.

Part of the HTP’s objective is to enforce collaboration between hospitals and RAEs; hospital leaders largely believe this endeavor has failed. There is scant belief that this collaboration has improved patient outcomes or that the RAEs are meaningfully utilizing data that hospitals provide. Also, RAEs are not financially accountable to the HTP like hospitals are. The data provided by RAEs are not transparent; they have no milestone reporting and little accountability for results.

Providers nearly unanimously agree that the HTP is a complex program to implement. It is not guided by objective evidence, lacks meaningful reporting requirements, has unclear governance and administrative processes, and largely does not support existing quality agendas. In many cases, the program does not align with impactful improvements for the care of patients. Hospital leaders also do not believe that the program has reduced the cost of care, lowered avoidable admissions, narrowed healthcare disparities, nor improved the overall effectiveness of care delivery, though all of those are goals of the program.

As a five-year program that launched in 2021, the HTP is up for sunset or reauthorization this year. For the reasons articulated above, many providers would prefer that the program not be renewed; if it is extended, however, there are opportunities for beneficial reforms. Policymakers could improve the HTP by allowing hospitals to lead it and letting HCPF act as a repository for data rather than a decision-maker. Reform should empower hospital leaders to propose meaningful quality measures and reduce administrative and technological burdens.

Medicaid Enrollment

Medicaid in Colorado covers disabled people, pregnant women, low-income adults and their children, and some seniors. Although the eligible population has generally risen over time due to coverage expansions (Colorado adopted Medicaid expansion in 2014) and demographics, enrollment in Health First Colorado has fallen in five of the last 10 years. By far the largest of these declines occurred between 2023 and 2025 when nearly 800,000 people were disenrolled from Medicaid following expirations of pandemic-related protections.[xvii] Colorado’s disenrollment rate through this unwinding period was well above the national average—according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 48% of eligibility redeterminations in Colorado and 31% across the country resulted in disenrollment.[xviii] These disenrollments brought Medicaid coverage in the state down to nearly its 2015 level by 2025.

For Colorado hospitals, these removals came at an inopportune time. Although Medicaid does not reimburse the full cost of most medical procedures, many of those disenrolled from Medicaid after the pandemic became uninsured and reliant on uncompensated care. Colorado hospitals provided $140 million in care to patients unable to pay during the first quarter of 2025 alone, a 26% increase over the same period in 2024 and double that of 2023.[xix]

Part of the reason for Colorado’s high disenrollment rate may have been how HCPF accommodated enrollees seeking renewals after the temporary federal Medicaid protections expired. Many states put emphasis on automating renewals whereas Colorado’s process was too complex for some enrollees to negotiate.[xx] In 2023, Colorado had approximately 608,000 children covered by Medicaid and just 420,000 a year later; this suggests that parents may have had particular trouble navigating the renewal process.

When people lose Medicaid coverage and become uninsured, the financial burden of caring for these patients shifts to private insurance, causing increases in insurance premiums. When insurance premiums get too high, people let their private coverage lapse, raising the uninsured population and degrading system-wide quality of care. This scenario may be playing out in Colorado now. From 2022 to 2024, total emergency room visits by uninsured patients in Colorado rose by 53%—an increase of more than 90,000. In metro Denver, the increase was approximately 67%. This rise indicates a lack of primary care access for this population, something Medicaid provides to its enrollees.

Recommendations

Given expected future budget shortfalls, policymakers must contain Medicaid costs while ensuring that quality of care across Colorado’s healthcare system does not diminish needlessly. Fortunately, there are opportunities to trim spending, reduce burdens on hospitals, and enhance patient care. Policymakers and HCPF administrators could:

- Reduce HCPF’s spending on priorities other than patient care

- Consider rolling back recent legislative actions that have increased costs for providers and/or HCPF

- Take a much more collaborative approach to its relationships with hospitals, be less bureaucratic, educate rather than penalize, and do away with regulations that add little value

- Take better advantage of SDPs

- Return the full value of underpayments to hospitals when found in RAC auditsEnd or reform the Hospital Transformation Program

- Make more of an effort to keep eligible people on Medicaid to manage providers’ uncompensated care costs

Conclusion

Colorado’s state-funded health care system is at a breaking point. For the last decade, policymakers have added burdens on providers, particularly hospitals, while approving significant funding boosts at HCPF that do little to improve care. The state Medicaid system is bloated, but not because of new enrollees. In fact, disenrollment in Medicaid may be leading to higher health care costs statewide.

Regulatory reform is necessary, and policymakers also should consider options to reduce HCPF’s budget while still providing care to the Coloradans who need it most.

[i] JBC Appropriations Reports

[ii] https://www.commonsenseinstituteus.org/colorado/research/healthcare/colorado-health-policy-at-a-crossroads-growth-costs-and-consequences

[iii] https://www.cbsnews.com/colorado/news/colorado-emergency-room-maternity-unit-close-hospitals-hemorrhage-money/

[iv] Joint Budget Committee appropriations reports

[v] https://www.kff.org/state-health-policy-data/state-indicator/total-population/

[vi] https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/national-medicaid-chip-program-information/medicaid-chip-enrollment-data/medicaid-enrollment-data-collected-through-mbes

[vii] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PCU622622

[viii] https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/

[ix] https://hcpf.colorado.gov/sites/hcpf/files/HCPF%20Department%20Performance%20Plan%20FY25-26.pdf

[xi] HCPF Budget Requests (Schedule 2)

[xii] https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/1/text

[xiii] https://hcpf.colorado.gov/sites/hcpf/files/CHASE%20SDP%20Proposal%202025%2006%2004%20%281%29.pdf

[xiv] https://content.leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/documents/audits/2356p_evaluation_hcpf_medicaid_recovery_audit_contractor_program_final.pdf

[xv] https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/SB25-314

[xvi] https://cha.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/02.25.25_HTP-Member-Survey-PPT-Final-New.pdf

[xvii] https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/10-things-to-know-about-the-unwinding-of-the-medicaid-continuous-enrollment-provision/

[xviii] https://www.kff.org/medicaid/medicaid-enrollment-and-unwinding-tracker/#8815e057-6ee9-4945-8ca1-705913d143b8

[xix] https://hcpf.colorado.gov/hospital-financial-transparency

[xx] https://www.denverpost.com/2025/09/17/colorado-children-health-insurance-medicaid/