Introduction

This paper is a complement to an earlier CSI study, “Do Traditional Public Schools Serve All Students?” that established the need for school choice options in Arizona. In this paper, CSI addresses the misinformation surrounding Arizona’s Empowerment Scholarship Account (ESA) program and explores Arizona’s history with non-education voucher systems, including publicly funded programs for housing, healthcare, welfare, transportation, childcare, and more.

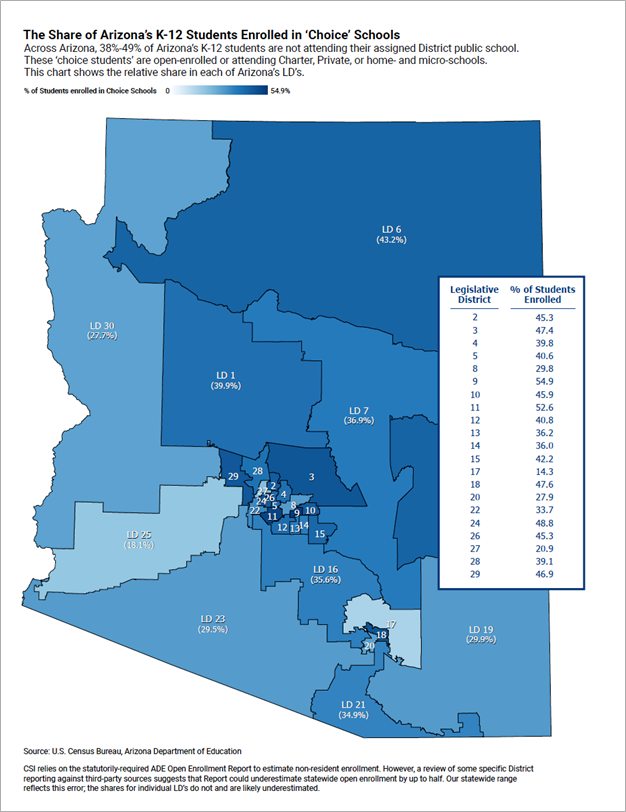

The paper’s purpose is to articulate the positive impact ESAs have had on all kinds of students – including Black, Brown, and special needs students and their families, and middle- and low-income families, and to demonstrate how ending the program would adversely impact these students and the state as a whole. Today, half of Arizona’s K-12 students participate in school choice; ending or restricting those options would raise costs for taxpayers, while hurting student achievement. One story in particular illustrates the effect an ESA can have.

Vanessa and Amani

Vanessa, a dedicated mother, faced numerous obstacles while navigating the traditional public education system for her daughter, Amani, who was born with Down syndrome. Despite Vanessa’s persistent advocacy, Amani’s emotional and academic needs were not adequately met, leading to frustration and concern for her future. Traditional public schools also failed to provide the safe and supportive learning environment that was necessary for Amani’s growth.

When Arizona’s ESA program was enacted, Vanessa seized the opportunity to apply for an account on Amani's behalf. As one of the program's early recipients, Amani received funding that allowed her to attend safe schools that provided her the emotional and academic support she needed. This shift provided Amani with a tailored educational experience and a learning environment where she felt understood and valued.

With the support of the ESA, Amani flourished. A curriculum designed to accommodate her learning style enabled her to engage with material in a meaningful way. Smaller class sizes allowed for personalized attention, ensuring her emotional and academic needs were prioritized. Vanessa noticed a remarkable change in Amani’s confidence and enthusiasm for learning, which had previously been stifled in the traditional public school system.

Amani successfully graduated from high school. Her story illustrates the profound impact that safe and supportive learning environments can have on special needs students, enabling them to thrive academically and emotionally in the moment while paving the way for future success and independence.

Key Findings

- Five percent of Arizona’s public school students are Black and half are boys. Black students receive more than 10% of all suspensions. Male students are the recipients of more than 70% of public schools’ most aggressive disciplinary tools, including suspensions and expulsions.

- Five Arizona traditional public school districts account for 20% of all suspensions and expulsions. These schools are disproportionately non-white and serve students from lower-income families.

- About half of all Arizona K-12 students are today enrolled in choice schools – Charters, private- and home-schools, or open-enrolled District students.

- The loss of school choice in Arizona, or students having to return to their assigned District schools, would have financial and academic consequences. CSI estimates this loss would result in 4.2% lower Reading scores and 4.0% lower Math proficiency across the state, and reduce the number of high school graduates by 24,000 over the next decade.

- At the same time, the costs to taxpayers would increase, even after accounting for any savings from eliminating ESA’s and STO’s – by up to $2.2 billion annually.

- Since January 2021, the BMF Microschools in the Phoenix area - affiliated with Rev. Janelle Wood, an author of this study - have served approximately 180 students in Central Phoenix. Ninety percent of these students are non-white and 100% were ESA recipients. Most came from households subsisting on lower-incomes, were struggling with disciplinary issues, or were behind in learning.

Historical Scholarship Use to Meet Family Needs

The United States has a long history of providing direct public financial assistance to the public, to help them cover all kinds of household costs deemed necessary and important. The country began to see the widespread introduction of vouchers for education in the mid-20th century with the GI Bill in 1944. Federal leaders continued to expand the use of vouchers in the 1960s and 1970s with the creation of the Section 8 housing voucher program and expansion of public welfare programs like the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, which helps families pay for basic needs.

In recent decades, government leaders have used voucher systems to provide a wide range of services, including childcare, healthcare, and transportation. The Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) provides vouchers to low-income families to help pay for childcare, for example, while the Medicaid program provides vouchers to help low-income individuals and families pay for healthcare.

Federal research indicates voucher programs have been instrumental in addressing the needs of families. For instance, a U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development report from 2015[i] found housing vouchers reduce homelessness and improve housing stability. Similarly, food vouchers are linked to improved health outcomes and reduced food insecurity.[ii] In the context of education, K-12 voucher programs have been associated with increased parental satisfaction and improved academic outcomes for participating students.[iii]

Arizona Has Used Vouchers to Fund Household Needs

Arizona has a long history of implementing vouchers, including for public scholarship and educational choice programs that provide options to Arizona’s residents from kindergarten to primary and secondary school and even beyond.

In the 1980s, Arizona became one of the first states to implement a housing voucher program. With the passage of Medicaid (today, the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS)) in 1982 and the Arizona Child Care Administration (ACCA) — both of which operate on a relatively open fee-for-service model — Arizona expanded its voucher programs to include welfare.

Today, the state provides vouchers to low-income individuals to help pay for transportation, for example, while individuals from households on the low end of the income spectrum are eligible for the Arizona Quest Card, an Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) card, that can be used to buy food at authorized stores and ATMs.[iv]

Despite Arizona’s history of providing publicly funded, voucher-like benefits, the state has seen resistance to providing publicly funded scholarships to Arizona’s K-12 students and their families. This opposition comes despite the fact that, as this paper will show, there is evidence and experience that indicates families are generally best able to make consumption decisions specific to their needs, while minimizing costs.[v]

A Short History of Education Vouchers in the United States

Private school voucher programs were initially designed exclusively and directly to provide support to help families afford private school tuition. Often, this meant the funding went from the state to the school directly. While this helped expand choice, it still codified a formal relationship between state and school, with the child and their family in-between.

In the 2002 case Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the constitutionality of a traditional school voucher program in Ohio under the First Amendment’s establishment clause.

In 2004, the U.S. Congress created the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program, the first and only federally private school choice program. At that time, there were not even many private school voucher models approved by state governments.

That changed over the next two decades. By 2023, the news outlet K-12 Dive reported there were 25 voucher programs in 14 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico that served more than 310,000 students. In that year alone, six states expanded or created school choice programs that use taxpayer dollars.[vi]

Beginning with Arizona’s universal program in 2022, Education Savings Accounts (ESA’s) began to radically change this structure - they guarantee each student access to a specific amount of taxpayer-funded money for their K-12 education. The student freely uses that money consistent with their choices and preferences, but subject to that states statutory requirements. Studnets can use ESA money at traditional private schools, but also to homeschool or attend alternative microschools. The education transaction becomes a private affair between student and education service providers; the states relationship is exclusively with the student and their family.

A History of School Choice Funding in Arizona

Scholarship Tax Organizations (STOs) Are Active in Arizona

Scholarship Tax Organizations (STOs) are nonprofit entities that collect donations from individuals and businesses that want to contribute to educational scholarships. Donors receive a dollar-for-dollar tax credit for their contributions against their state income tax liability, up to specified limits. However, the monetary benefit is not the only reason donors are attracted to STOs. These organizations also allow contributors to participate in the betterment of their community and to support a parents’ right to choose the best learning environment for their children.

Arizona’s STOs are overseen by state Department of Revenue and must adhere to specific regulations governing their operations.

Broadly, STOs empower families, particularly those from lower-income backgrounds, to gain access to, and benefit from, learning environments that may do a better job of meeting the academic and socio-emotional needs of students.

The structure of STOs allows for the pooling of funds from various sources, which are then allocated as scholarships to eligible students. STOs may offer scholarships based on need, academic merit, or other criteria established by the organization. Many STOs partner with private schools to facilitate the scholarship application process and ensure that awarded funds are used for tuition only.

Arizona’s STOs were created largely in response to the growing demand for educational alternatives to traditional public schools. The Arizona Legislature enacted the first STO law in 1997, providing a framework for individuals and corporations to contribute to scholarship funds that would assist students in paying for private school tuition. The program has undergone many amendments and modifications in order to help more students attend private schools.

STO scholarship eligibility is generally open to students who meet specific criteria established by an individual or organization. These criteria include, but are not limited to:

- Financial need. Many STOs prioritize students from low- to moderate-income families who may not otherwise afford private school tuition.

- Desire to leave underperforming public schools. Some scholarships are specifically designed for students currently enrolled in public schools or who choose to transition from public to private education.

- Age. STOs often specify eligible grade levels for scholarship recipients, typically covering K-12 education.

Additionally, some STOs may consider academic achievement or potential as part of their scholarship criteria.

While STOs are popular in Arizona, and, as Figure 1 illustrates, their constitutionality has been affirmed by the state supreme court, members of the legislature routinely introduce legislation to try to repeal Arizona’s law.

Unlike traditional school vouchers, STOs generally flow from the funding organizations to the private school. The governments involvement is limited to accrediting and regulating the Scholarship Organizations, but like voucher programs, an STO is required to provide scholarships directly to traditional private schools on behalf of beneficiary students.

Arizona’s Traditional School Voucher Program Struck Down

In 2006, the Arizona legislature created two $2.5 million direct appropriations to the Arizona Department of Education to create two voucher programs. One of the programs was to support students living with a disability. The other one was to support students who had been in foster care and were in the process of being adopted or placed with a guardian. Under these programs, the Arizona Department of Education made payments directly to schools and not parents.[vii]

Groups that opposed the programs sued in state court to end the voucher program, arguing the Arizona state constitution’s Blaine Amendment prohibited state funds from going to religious private schools. Even though similar amendments could be found in many state constitutions, and despite the fact that the U.S. Supreme Court in 2002 upheld the constitutionality of traditional school vouchers under the United States Constitution, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled against the two voucher programs on state Constitutional grounds.[viii]

After Vouchers Struck Down, State Turned to Scholarship Accounts

The Arizona Supreme Court’s decision to prohibit traditional vouchers provided the impetus to explore alternative models. Arizona created the nation’s first education savings account, known as Empowerment Scholarship Accounts (ESAs), in 2011.[ix] The program was initially designed to serve students with special needs. Reflecting the growing demand for educational choice, over the years lawmakers have expanded the ESA program to include a broader range of students.

Eleven years after ESAs were implemented, in 2022, the Arizona Legislature added Universal ESAs, making these accounts available to all K-12 students who are Arizona residents. (Students with a disability who are in pre-K also are eligible.)

Arizona’s ESAs are structured as state-funded accounts that provide families, especially low-income families who have historically been unable to exercise their right to choose, with a portion of the funding that would have been allocated to their child’s zoned traditional public school. Families can use these funds for a variety of eligible educational expenses, including private school tuition, tutoring, online learning programs, homeschooling curriculum, special education services, microschools, and other approved educational resources.

The ESA program is administered by the Arizona Department of Education, which oversees the application process, funding distribution, and compliance. Families must apply for an ESA and demonstrate eligibility to enroll. Once approved, the funds are deposited into a child’s Classwallet account that parents access to pay for eligible educational expenses.

ESA funding comes primarily from the state’s education budget. When a student is awarded an ESA, the state allocates a specific amount of funding - approximately 90% of the per-pupil funding amount that would have been allocated to the student’s zoned traditional public school. This funding, which for a typical student in 2024 would be about $7,000, is portable, meaning it follows the student to the learning options they choose. It is also perpetual – the student keeps the money, including any unused amount, in perpetuity to use for approved expenses.

While ESAs provide significant financial support for education and resources, the amount allocated may not cover the full cost of private school tuition or other learning expenses. A family may be responsible for supplementing the ESA. However, families may be eligible for additional funding if their child meets certain funding weight criteria allowed to other traditional public school students by state law, including having a disability diagnosis that requires supplementary financial support to provide an equal educational opportunity.

According to the Arizona Department of Education, as of 2021:

- 18% of students receiving ESAs had special needs.

- 56% of ESA students live in ZIP codes where the median income of families with at least one child is between $75k and $150k.

- 0.39% of students receiving ESAs were from failing schools.

- 1.23% of students receiving ESAs were from military families.

- 12.7% of students receiving ESAs were from rural areas.

- 0.44% of students receiving ESAs were from tribal nations.

Despite the ESAs’ popularity and success, state lawmakers routinely offer legislation to repeal or limit the program.

How ESAs Differ From Traditional School Vouchers

Arizona’s ESAs are not a voucher program in the traditional sense. That is because the state deposits public funds into an account for a family to use for a variety of education-related purposes — the state does not provide direct funding to schools.

As noted above, ESAs generally allow for a broader range of educational expenses families can use rather than solely to pay for private school tuition at traditional or selected private schools. Parents may utilize funds for homeschool curriculum, for example, or they can use it for behavioral health support, educational materials, microschools or other non-traditional private schools[x], and more.

In the United States today, there are ESA programs in at least 13 states that provide benefits to more than 340,000 K-12 students. [xi]

The success of Arizona’s ESA program and others, along with the fact that the program does not provide support directly to schools, have not kept legal challenges to the constitutionality of the program from coming, however.

As Figure 2 illustrates, there have been at least four lawsuits heard by the state Supreme Court.

Figure 2

In each case, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the ESA program. (As noted above, Figure 2 also shows the court ruled in favor of a scholarship tax credit in 1999.) Arizona courts have consistently found the ESA program does not conflict with the uniformity clause, Blaine Amendment, local control provision, or compelled support clause of the Arizona Constitution.

These rulings have affirmed the right of Arizona families to choose from among the vast educational options offered in the state, including private and religious schools, using ESA funds. So, what are those options?

Educational Options for Arizona’s K-12 Students

Traditional District Public Schools

Generally, the traditional public-school model operates within a framework characterized by three things: regional district school monopolies, funding mechanisms reliant on local property taxes, and attendance zoning primarily determined by zip codes.

This system in Arizona is organized into various school districts, each of which typically holds a monopoly over the education of students within its designated geographic area. This control means students are assigned to specific schools based on their home address.

While this system is meant to create a sense of community and convenience, ensuring students attend school close to home, it can reinforce inequalities. As in most states, Arizona public school funding largely relies on local property taxes, meaning schools in wealthier neighborhoods with higher housing values have larger budgets. These districts can afford to invest more in their schools while districts in other areas may struggle to provide basic resources. Indeed, schools in economically disadvantaged areas often hire less experienced teachers and have larger class sizes.

Figure 3

Despite these frustrating disparities, most families have no way out. Indeed, as Figure 3 shows, the vast majority of Arizona families still rely on traditional public schools even if their children are not well served in them.

District Public School Open Enrollment

In Arizona, the open enrollment model has become a prominent feature of school choice options, allowing parents greater flexibility in choosing out of district traditional public schools for their children. Open enrollment is designed to enhance educational options and foster competition among traditional public-schools, ultimately improving student outcomes everywhere.

The concept of open enrollment in Arizona gained traction in the early 1990s as part of a broader movement toward school choice. In 1994[xii], the Arizona Legislature passed the Open Enrollment Law, which enabled parents to enroll their children in traditional public schools outside of their designated traditional public-school districts. Under current law, parents can choose schools from different traditional public-school districts or even public charter schools.

Figure 4

Traditional public schools participating in the open enrollment program must adhere to specific guidelines, provide transparent admission policies, and ensure they do not discriminate against applicants. For reference, in the 2020-2021 school year, Black and Hispanic students only had an assessment passing rate of 25%, while their white peers had a passing rate of 53%. Further, Black students had the highest rate of suspensions at 34 students per 1000 receiving a suspension. The open enrollment system enables families to select traditional public schools based on various factors such as academic performance, program offerings, and school culture.

Funding for traditional public schools that participate in the open enrollment model is largely derived from state funding based on student enrollment numbers. When a student enrolls in a traditional public school outside their home district, the school that enrolls that student receives funding through the state's per-pupil funding formula. In other words: funding follows the student. This mechanism not only offers families more choices, it incentivizes public schools to provide a learning environment good enough to attract applicants and enrollees.

Since funding is based on enrollment, traditional public schools may experience a decrease or increase in revenue, which can impact their operational stability. Figure 4 shows the schools in Arizona that have attracted the most interest.

Public Charter Schools

With passage of the Charter Schools Act 1994, Arizona became the 11th state[xiii] to adopt charter school legislation.

Public charter schools in Arizona operate under a charter, which is a contract between the school and a charter authorizer that requires the school conform to certain academic, operational, financial, and philosophical rules. Charter authorizers can be school districts, universities, or a state board. Public charter schools may create their own curriculum and instructional and operational practices, but they are accountable for meeting specific performance metrics, such as academic achievement and student enrollment targets.

Figure 5

Public charter schools are funded through state education dollars based on student enrollment, with funding primarily derived from the state’s per-pupil funding formula. While public charter schools can access federal funding and grants, they do not benefit from local property tax revenues so they often have tighter budgets than traditional public schools.

Arizona’s public charter schools are open to all students, regardless of residential zip code. That said, public charter schools may implement their own admission processes, which can include lotteries when demand exceeds available slots. Some public charter schools also focus on particular educational themes, such as STEM, arts, or Montessori methods. As Figure 5 indicates, many Arizona families, particularly from marginalized communities, have chosen public charter schools.

Private Schools

Private schools in Arizona can be traced back to the late 19th century when various religious denominations sought to provide education aligned with their values. The first Catholic schools were established shortly after Arizona became a territory in 1863. Over the ensuing decades, other religious schools were established, reflecting a variety of beliefs. Secular private schools also began to appear, offering alternative educational philosophies and curricula that focused on academic rigor without a religious foundation.

Most private schools have specific admissions criteria, which may include academic assessments, interviews, and recommendations. Faith-based schools may also require families to adhere to the school’s religious beliefs or practices.

Families are typically required to pay tuition and additional fees to attend these schools. Financial aid or scholarships may be available to help offset costs, but eligibility for such assistance depends on financial need or merit.

Private schools in Arizona are primarily funded through tuition payments, donations, fundraising efforts, STOs, or ESAs.

While private schools have perhaps the longest formal history as school choice options in the contemporary American K-12 environment, the cost of private school tuition can be prohibitive for many families. Alternative schooling is often more attainable and realistic , and ESA’s – unlike traditional vouchers – acknowledge this reality.

Contemporary Homeschooling Movement

The homeschooling movement in Arizona began to gain traction in the 1970s and 1980s as families sought alternatives to traditional public and private schooling. Parents generally seek homeschooling because of the flexibility and autonomy. Families can choose how to structure their educational programs, leading to a diverse range of homeschooling approaches.

In 1993, the Arizona legislature passed laws recognizing homeschooling as a legitimate form of education and establishing guidelines. This legal recognition contributed to the growing acceptance and popularity of homeschooling in the state. A student is eligible to be homeschooled once their parents submit an “Intent to Homeschool” form to their assigned local school district. This notification is required annually.

Children must be between the ages of 6 and 16 to be eligible for homeschooling. There are no specific curriculum requirements mandated by the state, allowing families to choose educational materials and methods that align with their values and goals.

Funding for homeschooling in Arizona traditionally comes from families themselves. There are some mechanisms that provide support, however, including the tax credit for contributions to STOs. ESA funds also can be used to fund homeschool resources on a limited basis.

Microschools

The concept of microschools is rooted in the desire for smaller, more personalized learning environments that prioritize student engagement and individualized instruction. These schools often focus on project-based learning, interdisciplinary curricula, and community involvement, attracting families looking for tailored educational experiences for their children.

Microschools typically operate with a distinct structure that sets them apart from traditional public and private schools. Typically, they enjoy:

- Small class sizes of about 5 to 20 students per class, allowing for personalized attention and strong relationships between educators and students.

- Flexible learning environments that include the utilization of non-traditional learning spaces, which may include homes, community centers, or repurposed buildings. The flexibility helps create a more safe and supportive learning environment.

- Personalized curriculums that emphasize project-based learning, hands-on activities, and real-world applications and are tailored to meet the academic and socio-emotional needs and interests of students. Curricula may also integrate technology and interdisciplinary approaches in order to engage students actively.

- Deep community engagement. Students are encouraged to participate in local projects, internships, and service learning to connect their education with the world around them.

Microschools typically serve a range of grade levels, from preschool through high school. Blended learning environments are fairly common.

Each microschool may have its own admission criteria. Families interested in microschools often need to demonstrate a commitment to the school’s unique learning model, including active involvement in the educational process.

Many microschools charge tuition, which can vary depending on the school’s resources and offerings. Families are often responsible for paying tuition upfront.

Microschools may receive state funding through ESAs, public charters, and grants.

The financial sustainability of micro schools can be a concern, especially if they rely heavily on tuition and fundraising. Fluctuations in enrollment can impact their ability to maintain operations. Microschools also must navigate the regulatory landscape, including compliance with state education laws, health and safety regulations, and accountability measures.

Many families may be unaware of the microschool option, leading to challenges in attracting students and building a strong community presence. Microschools may face skepticism from those accustomed to traditional educational models, requiring ongoing efforts to demonstrate their effectiveness and value.

We have witnessed the power of ESA’s and the impact of the pandemic— the popularity of alternative- and home-schooling exploded after 2020, and starting in January 2021, through two Arizona BMF microschool campuses and one home-based microschool alone over 180 Arizona K-12 students have been served; 100% of these students are on an ESA, and many likely could not have afforded to attend without that support.

Myths about, and Resistance to, Arizona ESAs

Despite the success of ESA programs in Arizona and other states, there is a significant resistance to them. Critics argue ESAs divert much-needed funding from traditional public schools.[xiv] Research has shown that education savings account programs do not negatively impact public schools' performance or funding, however. [xv] (Additionally, K-12 grade funding for Arizona’s traditional public schools increased more than $6.3 billion between FY 2016 and FY 2025. (ESA funding has increased just $792 million over the same period.)[xvi]

Opponents also have argued ESAs exacerbate educational inequalities since low-income families may not have the same access to quality educational opportunities as their wealthier counterparts.[xvii] These claims also seem to be without merit. Indeed, studies show ESA programs can improve access to better schools for minority and low-income students[xviii] (2013). Anecdotally, a Black male student from Black Mothers Forum Microschools who started at the microschool in fourth grade and was reading below grade level is now in eighth grade and is reading at an eleventh grade reading level. ESAs provide new opportunities for low-income families who may be unable to afford private school tuition to utilize other educational options like homeschooling or microschools.

ESA opponents also cite worries about academic accountability, financial oversight, and student safety, but today’s ESA program has greater financial oversight than comparable public voucher and benefit programs identified in this paper.

[xix] Meanwhile, we know traditional public schools largely have left Black, Brown, and special needs students behind.

[xx] In general, ESA parents pull their children out of the traditional public school system because they want more academic accountability, safety, and financial oversight from their schools.

Figure 6

ESA Benefits for Families and Educators

ESAs offer parents flexibility and choice — and a sense of ownership and responsibility for outcomes. Parents can allocate ESA funds for a range of educational resources, allowing for a customized learning experience that meets the unique needs of their child. ESAs also provide much-needed financial support to families who would not otherwise have access to these choices. By making a tailored education more affordable for all, ESAs level the playing field.

With ESAs, certified teachers also can start their own microschools. Teachers want their students to learn and by giving educators the chance to expand their skills, work in a smaller learning environment, tailor their styles and curricula to particular students, and deepen relationships with students and families, they can better serve the community.

What if ESAs and School Choice Programs Went Away?

If school choice programs like ESAs and alternative schools were eliminated, based on its review of Census, Arizona Department of Education, and other publicly available data sources, CSI estimates more than 350,000 students would be forced back into a traditional public school system that has struggled to meet their needs. If traditional public schools had to absorb all students now participating in choice options, CSI estimates that average District public school class sizes would increase by up to 41% - from 17.7 to 24.9.[xxi] It is likely that everything from student academic performance and engagement, to their social-emotional wellness and school safety, would suffer.

Statistics, including graduation rates, bear out these assertions. The graduation rate for private school students in the Western Region stands at an impressive 96%. CSI assumes home school students graduate at the same rate as private school students. Meanwhile public school students in Arizona graduate at a significantly lower rate of 76.9%.[xxii] [xxiii] If all students were forced to attend traditional public district schools, CSI estimates there would be approximately 24,093 fewer high-school graduates over a 12-year span (one complete K-12 cohort). This decline in graduation rates is not just a number — it represents countless futures disrupted and potential unrealized.

Indeed, lower graduation rates harm the economy. A recent CSI study found fewer graduates entering higher education translates to a diminished workforce. In fact, if all students were to attend public district schools, CSI estimates that taxpayers would incur $2.2 billion in added costs.

Students’ academic performance would also suffer. Consider these numbers:

- Currently, 40% of all Arizona students are passing English Language Arts.

- That number is 48% for students in Arizona charter schools.[xxiv]

- In traditional public schools in 2024, Black Arizona students were passing English Language Arts at a rate of 29% and students with disabilities were passing at a rate of 11%.

- In Arizona charter schools, Black students were passing English Language Arts at a rate of 36% and students with disabilities were passing at a rate pf 15%.[xxv]

Various assessments, including the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), have consistently shown private school students outperform their public school counterparts. CSI estimates the aggregate statewide performance loss for all K-12 students would be at least 4.2% statewide for reading and 4.0% in math scores. Losses would be greatest for students previously enrolled in nonpublic schools.

Shifting more ESA and school choice students back to traditional public schools also may exacerbate inequities in discipline. That is because traditional public schools generally report higher rates of suspensions and expulsions than private institutions[xxvi]. Consider these numbers:

- In the 2017-18 school year, Black students made up 5% of students enrollment in Arizona, but received 11% of all suspensions, with the majority of suspensions being Black male students.

- Asian, Native American, or Pacific Islander students make up 11% of the traditional public school students in Arizona, but in 2017-18 made up 19% of suspensions and 16% of expulsions.

- Similarly, 5 Arizona traditional public school districts account for 20% of all suspensions and expulsions in Arizona. These schools are disproportionately nonwhite and have students who come from lower-income families.[xxvii]

Moving these children back to traditional public schools could subject them to a hostile and unsafe learning environment and lead to academic decline. The psychological toll of being in unsafe and unsupportive learning environments can be particularly detrimental to students who already face systemic barriers.

Next, the loss of educational choice could lead to a decrease in community trust and engagement. When families feel they have no say in their children's education, their connection to the school system weakens. This disengagement can ripple through the community, eroding the support systems necessary for fostering a thriving educational environment.

Finally, setting aside school choice programs would hit Arizonans in their wallets. We estimate moving students back into the public school system would cost taxpayers $2.2 billion. This is the additional burden on taxpayers from having over 350,000 Arizona students now attend traditional public schools. Assuming the level of teachers remained the same, CSI estimates that class sizes would increase 41%

if all school choice options were taken away.

Figure 7

The Bottom Line

It is clear traditional District public schools do not serve all students. Particularly since the pandemic, performance for many students – but particularly lower-income, nonwhite, and boy students – has collapsed. Surveys of parent attitudes reveal widespread and growing dissatisfaction with the classroom environment, curriculum, and safety standards of District schools.

As a result, students have been leaving their assigned District classrooms. In Arizona, today half of K-12 students are exercising some form of school choice. Arizona’s choice options – including open enrollment, state-licensed Charter schools, the STO program, and now its universal ESA program uniquely enables all families to actively participate in these choices, and keeps the states promise to provide a K-12 education to all of its children (wherever they go). The story about Vanessa and Amani at the outset of this report bears that out.

Appendix A: “Choice-Killing” Legislation in Arizona